It Starts With Verbs and Nouns

Roy Fielding’s REST work showed us that the design of the interaction between a client and a server could make a major difference to the reliability and scalability of that application. If you follow a set of conventions embodied in REST when designing your application, is means that (for example) the network will be able to cache responses to certain requests, offloading work from both upstream network components and from the application.

But REST was about more than performance. It offered a way of separating the actions performed by your applications (the verbs) from the things acted upon (the nouns, or in REST terms, the resources). What’s more, REST said that the verbs that you use should apply consistently across all your resources.

When using HTTP, the HTTP verbs (such as GET, PUT, POST, and DELETE) are also the verbs that should be used with REST applications. This makes a lot of sense, because things like routers and proxies also understand these verbs.

One of the successes built using these principles is the Atom Publishing Protocol. Atom allows clients to fetch, edit, and publish web resources. Atom is probably most commonly applied to allow people to use local editors to create and maintain blog articles—client software on the user’s computer uses Atom to fetch existing articles and to save back edited or new articles.

Let’s look at how that happens with Atom.

I fire up my Atom-based local client. It needs to fetch the updated list of all the articles currently on the server, so it issues a GET request to a URL that represents the collection of articles: the verb is GET, and the resource is the collection.

GET /articles

What comes back is a list of resources. Included with each resource are one or two URIs. One of these URIs can be used to access that resource for editing. Let’s say I want to edit a particular article. First, my client software will fetch it, using the URI given in the collection:

GET /article/123

As a user of the editing software, I then see a nicely formatted version of the article. If I click the [EDIT]button, that view changes: I now see text boxes, drop down lists, text areas, and so on. I can now change the article’s contents. When I press [SAVE], the local application then packages up the changed article and sends it back to the server using a PUT request. The use of PUT says “update an existing resource with this new stuff.”

Browsers are Dumb

If you use a browser to interact with a server, you’re using a half-duplex, forms-based device. The host sends down a form, you fill in the form, and send it back when you’re ready. This turns out to be really convenient for people running networks and servers. Because HTTP is stateless, and because applications talk to browsers using a fire-and-forget model, your servers and networks can handle very large numbers of devices. This is exactly the architecture that IBM championed back in the 70s. The half-duplex, poll-select nature of 3270-based applications allowed mainframes with less processing power than a modern toaster to handle tens of thousands of simultaneous users. The browser is really not much better than a 3270 (except the resolution is better when displaying porn). (Recently, folks have been trying to circumvent this simplicity by making browser-based applications more interactive using technologies such as Ajax. To my mind, this is just a stop-gap until we throw the browser away altogether—Ajax is just lipstick on a pig.)

How well do browsers play in a RESTful world?

Well, for a start, they really only use two of the HTTP verbs: GET and POST. Is this a problem? Yes and no.

We can always hack around the lack of verbs by embedding the verb that you wanted to use somewhere in the request that you send to the server. It can be embedded in the URL that you use to access a resource or it can be embedded in the body of the request (for example as an element of the POST data). Both work, assuming the server understands the conventions. But both techniques also mean that you’re not using REST and the HTTP verb set; you’re simply using HTTP as a transport with your own protocol layered on top. And that means that the network is less able to do clever things to optimize your traffic.

But a browser talking HTML over HTTP is also lacking in another important area. It isn’t running any application functionality locally. Remember our Atom-based blogging client? It had smarts, and so it knew how to display an article for editing. Browsers don’t have that (without a whole lot of support in terms of bolted on Javascript or Flash). So, as a result, people using RESTful ideas to talk to browsers have to put the smarts back on the server. They invent new URLs which (for example) return a resource, but return it all wrapped up in the HTML needed to display it as a form for browser-based editing. This is how Rails does it. Using the Rails conventions, if I want to fetch an article for viewing on a browser, I can use

GET /article/1

If, instead, I want to allow the user to edit the resource, I issue

GET /article/1;edit

The application then sends down a form pre-populated with the data from that article. When I hit submit, the form contents are sent back to the server, along with a hidden field that tells the server to pretend that the HTTP POST request is actually a RESTful PUT request—the result is that the resource is updated on the server.

The ;xxx notation looks like it was tacked on. I think that in this case, looks aren’t deceiving—these modifiers really were something of an afterthought, added when it became apparent that a pure Atom-like protocol actually wouldn’t do everything needed in a real-world browser-based web application. That’s because the client of an Atom server is assumed to be more that just a display device. An Atom client would not say “fetch me this resource and (oh, by the way) send it down as a form so that I can edit it.” The client would just say GET, do what it had to do, then issue a PUT.

So, in pure REST, the client is a peer (or maybe even in charge) of the interchange. But when talking to a dumb browser, the client is no better than an intermediary between the human and the application. That’s why it was necessary to add things such as ;edit.

Client-independent Applications

One of the other benefits of designing your applications against the limited verbs offered by HTTP REST is that you can (in theory) support many different clients with the same application code. You could write blogging server that (for example) looked at the HTTP Accepts header when deciding what to send back to a client. The response to a GET request to /articles could be a nicely formatted HTML page if the client wants an HTML response, an XML payload if the client asks for XML, or an Atom collection if the client asks for application/atomcoll+xml. In Rails terms, this is handled by therespond_to stanza that is duplicated in each controller action of a RESTful server.

But the benefits run deeper than simply being able to serve up different styles of response.

The HTTP verb set maps (with a little URL tweaking) pretty nicely onto the database verb set. POST, GET, PUT, and DELETE get mapped to the database CRUD verbs: Create, Read, Update, and Delete.

So, in theory at least, you should be able to write your application code as a fairly thin veneer over a set of resources. The application exports the verbs to manipulate the resources and the clients have fun accessing them. This is similar to the vision of Naked Objects.

However, I personally think it was optimistic to try to treat the two styles of interaction (smart and dumb clients) using the same protocol. The ugliness of the ;xxx appendages was a hint.

I think there’s a lot of merit in following a CRUD-based model for interacting with your application’s resources. I’m not convinced all the hassle of bending dumb browser interactions into a REST-based set of verbs, and then extending those verbs to make it work, is worth the extra hassle. To put it another way, I believe the discipline and conventions imposed by thinking of your application interface as a RESTful one are worthwhile. They lead to cleaner and easier-to-understand designs. The hoops you have to jump through to implement it with a browser as a client seem to suggest that a slavish adherence to the protocol might be trying to push it too far.

An Alternative Model

Does that mean I’m down on the RESTful, CRUD based approach to application development? Not at all. For some categories of application, I think it’s a great way of structuring your code. But REST isn’t designed for talking to people. So let’s accept that fact when creating applications. And, while we’re at it, let’s take advantage of the fact that HTTP is such a flexible transport. Rather than trying to design one monolithic application than has both the CRUD functionality and the smarts to be able to talk HTML to end users, why not split it into two smaller and simpler applications?

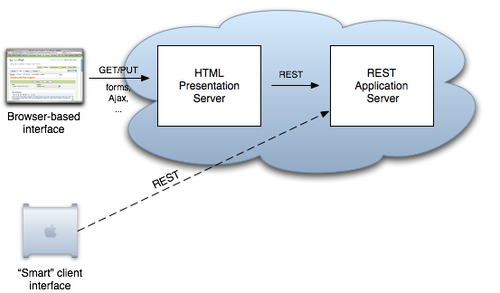

Put the main application logic into a RESTful server. This is where all the CRUD-style access to resources takes place.

Then, write a second proxy server. This is an HTTP filter, sitting between dumb browsers and your core resources. When browser-based users need to interact with your resources, they actually connect to this proxy. It then talks REST to your main server, and interprets the RESTful responses back into a form that’s useful on the browser. And this filter doesn’t have to be a dumb presentation layer—there’s nothing to say that it can’t handle additional functionality as well. Things like menus, user preferences, and so on could all sit here.

Where does this filter sit? That depends. Sometimes it makes sense to have it running locally on the user’s own computer. In this case you’re back in a situation like the one we looked at with the blogging software. Sometimes it makes sense to have the proxy running on the network. In this case you gain some interesting architectural flexibility—there’s no rule that says you must colocate your REST and presentation servers. Potentially this can lead to better response times, lower network loads, and increased security.

With this approach, we can lose all the hacks we need to make to our URLs and POST data to make them act RESTfully. And we can lose all the ugly respond_to stanzas in our Rails server code. We might even be able to get better reuse, sharing both resource servers and presentation servers between applications.

Let’s call it RADAR. We have a RESTful Application talking to Dumb-Ass Recipients.

Does it work? I don’t know. You tell me.

No comments:

Post a Comment